A reader recently asked me about the Hawaiians who lived in Kalalau valley before and the “hippies” who live there now:

I know Hawaiians previously lived in the valleys, but after it became illegal, they left. Or did they?

I’m not certain about exact dates, but here is a rough timeline. What’s not exactly clear is when and how it became illegal to live in Kalalau.

Historically, Hawaiians lived in certain valleys that could support them (Kalalau was the biggest, but also Honopu, Nualolo, and maybe a few people in others). They created terraces and grew either taro in irrigated plots or dry-land yams, in addition to fishing. Much of the valleys were deforested, and I’m not quite sure what they did for fuel (I never thought of it before, and I’ve never heard anyone speculate on that). I know they had treacherous trails down from the forest in Kokee, so maybe they carried bundles of wood down.

In any case, archaelogists estimate up to 2000 people could live in Kalalau, which I find plausible. I suppose that was before 1800. After the subsistence agricultural society had been displaced by the commodities and merchandise-based economy brought by the missionaries and whalers, farms were abandoned, especially in the hard-to-reach valleys. I think they must’ve still been inhabited in the late 1800’s, as demonstrated by the famous story of Koolau the leper who hid out in Kalalau with other lepers who didn’t want to be sent away.

By the 1900’s, I think the smaller valleys (Nualolo and Honopu) were abandoned. Kalalau was accessible by trail and had more water, so I think people still lived there. The land was sold to one of the big families on the island (not sure of the details, but it may have been the Robinsons), and it became grazing land for cattle. So there must have been a few people running cattle there, probably living seasonally with a few fruit trees and vegetable garden. Incidentally, they used to drive the cattle in and out on the Kalalau trail, sometimes losing one over the edge–and I’m not sure if they also got the cattle in and out by boat–seems like a lot of trouble to me.

I met a local in Kalalau who claims his Aunty was the last person to live in Kalalau, and I suppose that was in the 30’s or 40’s. Sometime after that, it became a state park, and parts of the Kalalau trail became nature reserves (though hunting is still allowed in many areas, so it’s not just tourists on the trail). In the 50’s and 60’s, an African-American doctor retired/gave up his practice and became known as the hermit of Kalalau, in the pre-hippie era. In the 70’s, the hippies were all over Kauai, especially at Taylor camp at Haena, and I’m sure many of them moved to Kalalau when the camp was shut down.

I’m not quite sure of the circumstances, but I suppose 20-50 people lived in Kalalau quasi-permanently over the 70’s. I don’t know if it was tolerated, ignored, or just plain unknown to the park administrators. Nor do I know if they more or less left by themselves or were forced out. I think by the 90’s, there were less permanent residents, probably 10-20, with various free spirits adopting it as home for months at a time before moving on. When I first went in early 2000’s, I think there were less than 10 real residents, with a few people migrating in and out over the seasons. Some of them live by growing weed for sale, as well as collecting welfare, and carrying supplies into the valley.

Does anyone live along the Na Pali? Aside from the legalities, could they?

I do know that over this decade, the park service has totally cracked down on the residents, evicting nearly all, some by force and commando-style. But I get the impression that a small core remain, both hiding up in the furthest reaches, and also grudgingly allowed by the park rangers. They sort of position themselves as care-takers, not trashing the place and keeping out or reporting the inevitable whackos who show up and try to move in. The local guy I met didn’t live there himself, but use to boat in and out regularly to camp, hang out with the residents, resupply them, and carry out trash. I think he was tolerated as well, up to a point.

There was another local of Hawaiian descent who would live there for weeks at a time and claimed to be a caretaker of the spiritual locations in the valleys (old heiau). The park service cracked down on him pretty hard, because he was openly flaunting the permit system and authority of the parks, even though he was doing no harm.

Because Kalalau was historically an agricultural valley, there was one experiment of allowing a caretaker to go in and replant a taro and vegetable patch, sort of as a token gesture to the Hawaiian community. I saw the patch growing once when I was there, but I never saw the people. I don’t think the park continued the experiment, because I’m fairly sure it does not sanction anyone living there now.

So there you have a short overview. Moving into Kalalau is certainly possible, people do it all the time even today, but it tends to be more limited and mostly under fear of being chased by rangers. The rangers come in by helicopter and chase down any “residents” they can catch, so they’re really cracking down, or at least appearing to do so.

A recent comment also asked about the famous library of Kalalau:

I was wondering…I have heard there is a “library” in the valley….a bunch of paperbacks under a tarp….Does it exist and if so… how do you find it. I love to spend time reading…finding a great spot, soak up the beauty and share it with a book but they are HEAVY and if there are books to borrow I would love to do so. What can you tell me?

I believe it was the hermit of Kalalau mentioned above who started the library in the cave he lived in, which I gather was the first sea cave. I imagine that the various people living in the valley after him either kept his books or started new collections. When the rangers raided the valley these past years, I heard they dismantled whole encampments, and that probably included some books. But I don’t know if there was still a big library or whether it survived.

When I was there last year and talked with some of the residents, it sounded like there were still books around, but whether that was the main library or just little collections, I could not tell. What I do know is that it’s not a public library with borrowing privileges. You would need to meet and befriend one of the locals before you would have a chance at receiving any book they might have. And I doubt you would get to see or browse the “library” itself, if it still exists; I think they are much more particular about their hiding places now. However, once you break the ice with them, they tend to be very generous, so who knows what you will find.

Generous or not, it would still be a nice gesture if you brought a book with you and offered it to someone there. Paperbacks aren’t that heavy and are usually small enough to pack on the trail. That might be the best way to open the doors to the library. (Then again, if everyone who reads this and takes a book in, the residents are going to start wondering what the big deal is.)

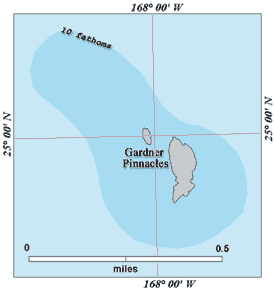

The degree confluence closest to land in Hawaii is far from the accessible islands. It occurs a few dozen feet from shore, right between the emergent rocks of the

The degree confluence closest to land in Hawaii is far from the accessible islands. It occurs a few dozen feet from shore, right between the emergent rocks of the