The other post about the trail’s history got too long, so I’ll put the maps and photos in this new post.

I first walked the trail in September 2005, when it’s future was uncertain. I mapped the trail with my GPS to record its exact location. I didn’t blog about the path at the time because the landowner was still claiming there was no path, and should he prevail, access would thus constitute trespassing. I did blog about the charms of Moloa’a beach, although the bay deserves another post and more photos one of these days.

Then I got busy with other projects and didn’t hear about the Moloa’a trail again until last month. The trail had “survived” the permitting process, with the landowner recognizing a trail inland from the rocky shore and rising up to the mid-level bluff. However, there was rumor that it wasn’t the original trail, so I went back with the GPS and a camera to find the original trail again. Without further ado, here is what I recorded:

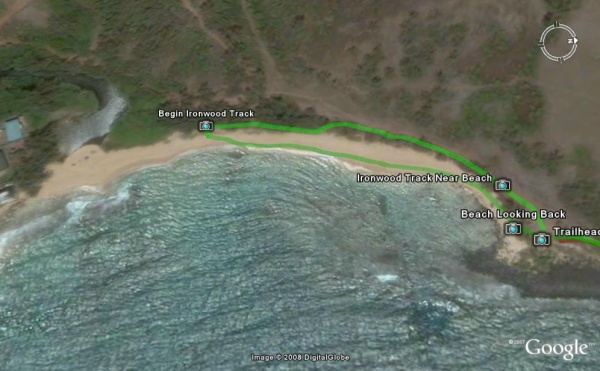

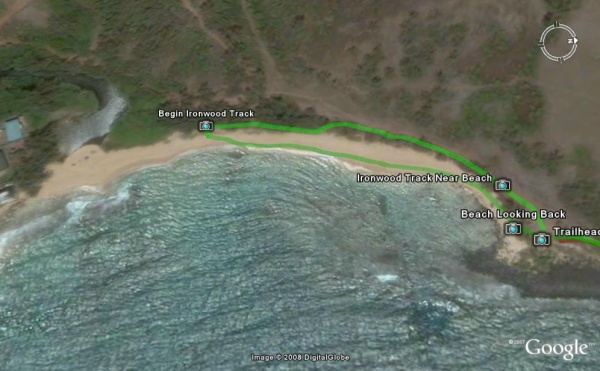

The faint green trail is the one I recorded in 2005. The red trail is the new one I walked earlier this month, and the brighter green trail is my attempt to find the original trail again, based on the sections that remain and the guidance of the old GPS track. The camera icons correspond exactly to the locations of the photos below. You can download the map with all its features if you have Google Earth installed on your computer.

What I found was indeed a new trail, parallel to the original trail, but 10 to 50 feet closer to the ocean. Normally, I would be excited about a new trail on Kauai, but this is just the wrong trail for all the wrong reasons.

First, the signage. This sign greets the hiker, and while it doesn’t signify an official trail, it pretty much acknowledges that people habitually walk here. However, I’m sure the landowner appreciates the official admonition to “stay on the path,” for the sake of the birds, of course.

Further on, and barely visible above, another sign placed by the landowner says “Please stay on trail, Mahalo.” These signs are strategically placed anywhere it would seem natural to walk in the direction of the original trail. What I found is that the new trail, being closer to the ocean in this low area, is on slightly slanted ground and just doesn’t feel like a good trail. The original trail however, walked by generations, had naturally adopted the “path of least resistance” where it felt safest and easiest to walk.

However, the land owner really doesn’t want people on the original trail. Here is evidence of a deliberate attempt to cover up the original trail: several large branches were laid in the trail such that they blocked the passage, but in a way made to look like overgrown bushes.

The photo above is looking backwards, just after the new trail splits off from the old trail behind the standing tree. It was taken from the new trail, looking at where the original trail used to be between the tree and the rock. The large branches have been placed so that the tangle of branches makes original trail impassible. Searching all the tall ironwood trees nearby, I could not see any branches or stumps where these might have been trimmed from, so I have to assume they were deliberately placed here.

Further on, and still before climbing to the bluff, the two trails almost come together again. I walked up to stand on the original trail, and looking back, I could clearly see the original route. Here in the shade of the tree, the trail was open, but in the distance you can see it was starting to grow over with grasses and shrubs.

The picture below is taken from the new trail in the same area, looking at the continuation of the original trail. You can see the flat tread of the original trail, compacted by generations of feet and resisting erosion. The original trail used to continue between the bright green shrubs and climb to the bluff at the low notch. When I hiked here 2 years ago, there was a short switchback to make the climb less steep, and the trail went through an opening under the taller trees at the crest of the bluff.

By contrast, the new trail was carved out of the rocks and shrubs on the exposed side of the bluff, in a straight, steep line to the top edge. It’s hard to tell the steepness of the trail in the images below, but it’s enough to really start pulling on your calves as you go up. I worry about the erosion on this steep new trail, not for the trail itself, but for the scar it could leave on the slope.

This is the view back down the new trail. You can see the rocks of the previous image at the bottom, with the new trail veering left out of sight towards the ocean and the original trail from 2 images above straight ahead.

|

Then it gets steeper as it climbs right between these large rocks. This image is also looking back down the trail, after just climbing up 10 feet.

|

Up on the bluff, which is actually just a “bench” halfway up the full bluff, is where the new trail robs the hiker of all the charms of the original trail. The new trail was created through the shrubs and small trees that cling to the edge of the bluff, where the footing is rocky and not always flat. There are two spots where the trees have not taken hold that afford a restricted view of the ocean. Then, new signs remind the unsuspecting hiker to go back into the thicket:

By contrast, the original trail crossed the bluff much further inland, through the relatively flat, grassy and open area that probably used to be a marginal pasture. The view of the ocean and Moloaa Bay is all around one side, and albatrosses and frigate birds swoop by as the ride the wind over the bluff.

In the picture above, you can see the flat, faintly worn path through the grass as it veers to the left to cross the pasture without losing altitude. Straight ahead in the trees, you can see the new trail sign from the previous picture.

It is obvious to me that the original trail crossed through this grassy area, not at the edge of it. Who would want to walk in the trees when you can be out in the open with beautiful views? As a hiker, I know the open is much more preferrable, giving you a place to observe the weather patterns on the horizon and a nice place to stop and rest. This is what the landowner is trying to take out of the public domain, to increase the “privacy” and value of the planned development.

At the end of the bluff is the makeshift shrine below. It changes every time I see it, as the wind knocks over the piles and people add bits of coral and shells. It is definitely a modern artefact, but I would not be surprised if it were also a site used by Hawaiians, either as a fishing shrine or just a fish lookout.

The new trail arrives directly at the shrine and contines into the trees again on the other side. When I hiked here in 2005, I was intrigued by the shrine and walked down here from the pasture. Thinking the trail might continue from here, I looked for it in the trees you see here, where the new trail is now. But at the time I didn’t find any path and had to walk back up to the pasture to find the continuation around the bluff, a detour you can see on the map of my original GPS track. To me, that is proof that the historical trail went directly through the pasture, not down in the trees as the landowners want us to believe.

Trail Continuation

This post is very long already, but for completeness, I must add two sections about the trail continuation and trailhead access.

The new trail joins the original trail in a wooded slope after leaving the grassy bluff. From here there is only one trail, what I call the original trail from my 2005 survey. However, there is some doubt as to whether it is the historical trail, as I have not heard from the Moloaa kupuna (elders) about their memories of this section.

To see the map below, as well as the archaeological map overlay mentioned below, download my map file and when it opens in Google Earth, expand the contents with the + icon and place a checkmark next to the corresponding folders to make them visible.

From the grassy bluff area, the trail turns out of Moloaa Bay to follow the north-east facing ocean bluff. The slope of the bluff here is moderate, and instead of climbing to the flat area at the top or the rocks at the bottom, the trial crosses the slope on a course with small dips and rises. At first, the trail dips down a little through some overgrown brush (this image is looking back towards the shrine):

The tread of the trail is still very good, so it’s easy to find. Further along, the trail is not so evident as it goes up and down to find passage between the ironwood.

Finally, the trail reaches some large rocks and a tangle of barbed wire that mark the property line. There are some great views of the reef and a little pocket beach in the cove, although Larsen’s beach is hidden beyond the far point.

I could not find the trail beyond this point, even though it is known to go to Larsen’s beach on a similar undefined easement through the neighboring property. Perhaps modern hikers have been enjoying the trail only as far as the great views back at the open meadow, and so the continuation is overgrown. Another possibility is that the archaeological map in my previous post shows the trail dipping back down to the ocean here, not crossing the slope of the bluff.

The historical trail on that map disagrees with my survey in other ways. For example, it crosses the grassy bluff even further inland and uphill from the original trail, but that path would have more ups and downs compared to the flat, controuring trail that was evident in 2005. However, the possibility that the trail went back down near the ocean has two supporting points: the reef does begin below the rocks at the property line, and the trail that was so evident even when overgrown doesn’t seem to continue in the trees. Perhaps the trail did begin to angle downwards through the overgrown area, to access the reef and skirt the rocky shorline all the way to Larsen’s—there is more trail discovery awaiting the adventurous hiker.

Trailhead Access

At the other end, there is also some uncertainty about where the trail begins. To access the trail, you would park along the left branch of Moloaa Rd. and then walk down to cross the stream at the beach. Facing the bay, the trailhead sign mentioned above is at the end of the sandy beach to your left. However, there could be an alternative to walking in the sand:

After a short walk on the beach, you will see a clearing under the ironwood trees with a No Tresspassing sign—this is the same landowner who is developing the bluff area.

Off to the left of the photo above, there used to be customary access to the beach from a county road that crosses the stream further up the valley, but the landowner put up a gate. I think the legal argument is that only the people who had customary access, the local fishermen mostly, would still be allowed, not the general public. I can understand the logic from a property owner’s point of view, but I don’t know if it’s valid.

The slope going uphill to the right used to be the road to access the pastures in the bluff area. I once thought that maybe the historical trail would follow that easy route, but from Google Earth it looks like that road is longer and has more ups and down than the original trail I mapped. And now that road has been cut by some bad erosion in a gully.

However, off to the right foreground of the photo above, is a narrow track that is parallel to the beach, but underneath the canopy of mature ironwoods. The track is mostly used by the land managers who get around on ATVs, but it is a nice path on a bed of ironwood needles, not muddy. Here you see a point where the track goes close to the beach, in fact there is evidence that storm waves wash over the track at this point:

What that image also shows is that it’s much easier to walk or hike on the track. Of course, walking barefoot on the beach is great, but it’s a long beach (almost a quarter-mile or 400m) with many rocks and a big slant at certain times of the year, as shown in the following photo looking back:

If Hawaiians needed to use the trail during stormy weather, it’s likely the beach was awash with waves, and they would have used a path through the vegetation (ironwood were imported and grew later). However, the archeolgical map does not show the historical trail in this area. As it stands now, the landowner seems to be claiming that track as private (and it is mostly above the highest wash of the waves), and the property managers would probably ask you to leave if they found you there. I think it would be a great addition to the trail if this section were clearly opened, providing a firm all-weather path nearly all the way. It would be even better if the old beach access were open again as well, given that the stream is difficult to cross at certain times of the year.

Conclusion

In the end, I think the whole issue about the trail is a question of respect. Does the landowner respect the historical, traditional, and legal rights that come with the land? By building a fake trail that lacks the safety and scenic benefits of the original trail, and then trying to obliterate the original trail, the landowner is showing total disrespect. Property rights are not absolute, even in the United States, and respecting the community and natural envirnomnent where you buy land, speculate, and develop property would seem to me the right thing to do.

For example, the landowners at the Kealia Kai development, just north of Kealia beach, donated the old cane road along the coast to the county. That area can now be accessed easily on the new bike path, soon all the way to Donkey beach, and I hear the owners got a huge tax write-off. I still think the houses being built at Kealia Kai will encroach on the natural setting, but I feel the developer did the right thing by also allowing public access to be improved.

The Moloaa trail has long been neglected by property owners and government oversight, tended to by only a few old-timers and hikers. It’s time to recognize it’s cultural and environmental value and give the public access to one of the few remaining historical trails on Kaua’i, if not the only one, and a beautiful one at that. My dream is that the trail be restored and reopened fully in it’s original path, and that it will become the first segment of a longer coastal trail, perhaps even connecting to the future bike path in Anahola.

Update

Two days after publishing this, I found out more details about how the new trail came to be in those 2 years I wasn’t paying attention (that’s why I’m blogger and not a journalist).

Environmental groups such as the Sierra Club were pushing the landowner to recognize the trail on the bluff in order to fulfill the public easement requirement of the land deed. But getting the state Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) to send out a surveyor to document the trail was proving to be impossible. Pulling a trick on everyone, the landowner quickly had the trail surveyed at his own cost and submitted it to the DLNR’s Na Ala Hele office which manages public trails. Obviously, the trail surveyed was the bad, new one in the trees and on the steep slope, but it was officially accepted over the objections of the Sierra Club.

As a result, the bad trail is now the one recognized by the state agency as the public easement, and there seems to be no recourse. I still wonder if the landowner needed a special permit to create the trail that did not exist before. The other permit applications were dropped recently, so apparently there is not going to be a privacy hedge mauka of the new trail, which is fortunate because it would have obliterated the historic trail.

There seems to be an odd situation here, because the historic trail still has some legal existence. Hawaii’s state constitution apparently guarantees residents of Hawaiian ancestry cultrual and customary access to Hawaiian sites, which if I understand correctly, includes access over private land. So I am told that non-Hawaiians who attempt to follow the historic trail can rightfully be asked to leave, but not native Hawaiians. I wonder what the state’s Office of Hawaiian Affairs would think of the attempts to block the trail with branches.

So it would seem that my dream of having the original trail restored is administratively hopeless. Furthermore, trespassing by non-Hawaiians would just justify the landowner’s claim that a fence or hedge needs to be built, which would destroy the natural openness of the area. So I cannot encourage most people to go looking for the original trail, they risk being confronted for trespassing. But perhaps it can be preserved if people of Hawaiian ancestry are made aware of their right to walk the historical trail and how easily it could be lost.